FAMILY OBITUARIES

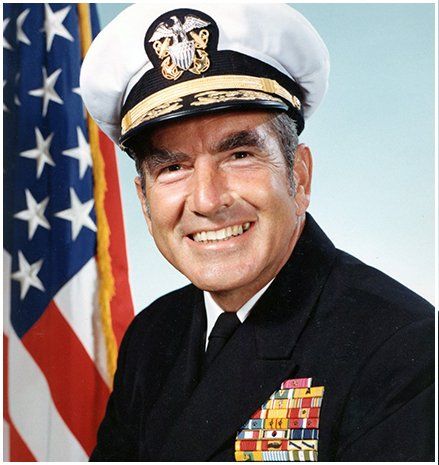

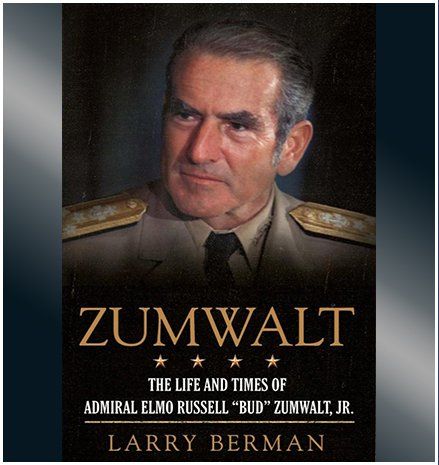

ADMIRAL ELMO RUSSELL ZUMWALT, JR.

29 November 1920 - 2 January 2000

Adm. Elmo R. Zumwalt Jr., who as chief of naval operations in the early 1970's ordered the Navy to end racial discrimination and demeaning restrictions on sailors, then faced a haunting personal anguish that he attributed to the defoliant Agent Orange, died yesterday at the Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C. He was 79 and lived in Arlington, Va.

The cause was complications from surgery for a chest tumor.

In July 1970, when Admiral Zumwalt, at age 49, became the youngest man to serve as the Navy's top-ranking officer, re-enlistments were plunging in the face of the war in Vietnam.

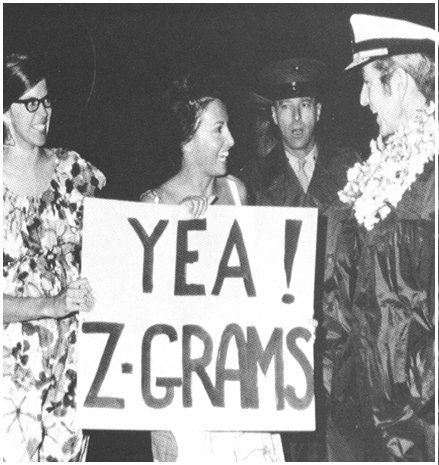

Hoping to again make naval service an appealing career, Admiral Zumwalt over the next four years issued 121 directives known as Z-Grams, which sought to change the way the Navy had done things for almost two centuries.

Critics, including many retired admirals, said that Admiral Zumwalt had created a permissive atmosphere endangering discipline, accusations that were fueled by racial incidents on the aircraft carriers Kitty Hawk and Constellation in 1972.

Admiral Zumwalt felt the antipathy toward his changes reflected racial prejudice, and in November 1972 he accused senior officers of ignoring his directives.

Despite resistance, he made progress as chief of naval operations: re-enlistments by first-term sailors rose, the number of black personnel increased, and Samuel L. Gravely Jr., became the first black to be appointed an admiral.

Admiral Zumwalt retired in 1974, but a decade later he was back in the public eye, enmeshed in family anguish arising from the Vietnam War.

While serving as commander of American naval forces in Vietnam from 1968 to 1970, he had ordered the spraying of the defoliant Agent Orange in the Mekong Delta, seeking to deny cover to snipers on the river banks.

One of the Navy boats patrolling the rivers and canals was commanded by his son, Lt. Elmo Zumwalt III.

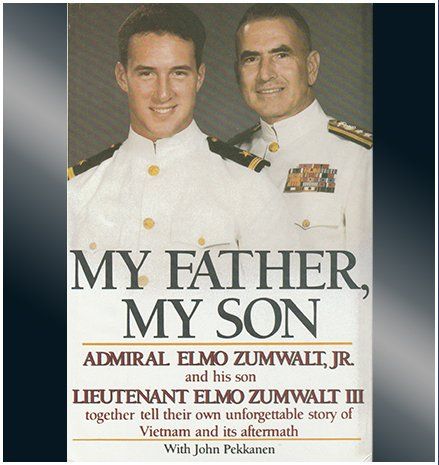

The two wrote a book, My Father, My Son

(Macmillan, 1986), telling of the younger Zumwalt's battle with cancer that both attributed to dioxin, the toxic byproduct of Agent Orange.

The story was made into a movie of the same title for CBS, which was shown in May 1988. Three months later, Elmo Zumwalt III died of cancer at age 42.

President Clinton said in a statement yesterday that Admiral Zumwalt ''worked vigorously to improve our sailors' quality of life and devoted himself to eliminating discrimination in the Navy.''

''Admiral Zumwalt became a great champion of veterans with war-related health problems,'' Mr. Clinton said. ''He established the first national bone marrow donor program to help cancer patients.''

Elmo Russell Zumwalt Jr. was born in San Francisco on Nov. 29, 1920, the son of doctors, and was reared in Tulare, Calif.

He graduated from the Naval Academy in 1942, won a Bronze Star serving on a destroyer in the Battle of Leyte Gulf in 1944 and served on the battleship Wisconsin in the Korean War.

In the early 1960's, he came to the attention of Paul H. Nitze, a foreign policy adviser in the Kennedy administration, after writing a paper on Soviet politics at the National War College.

During the Cuban missile crisis he was an aide to Mr. Nitze, who was assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, and when Mr. Nitze became secretary of the Navy in 1963, he was his executive assistant.

On Mr. Nitze's recommendation, he was named a rear admiral in 1965, at age 44 the youngest officer ever to attain the rank.

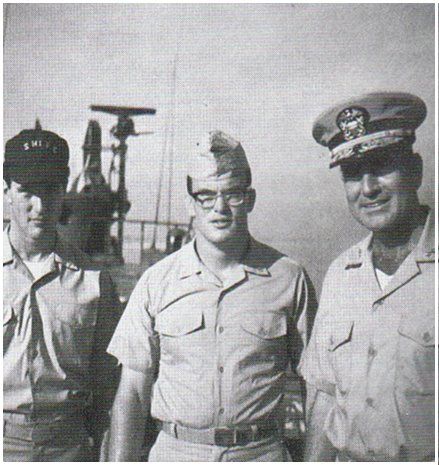

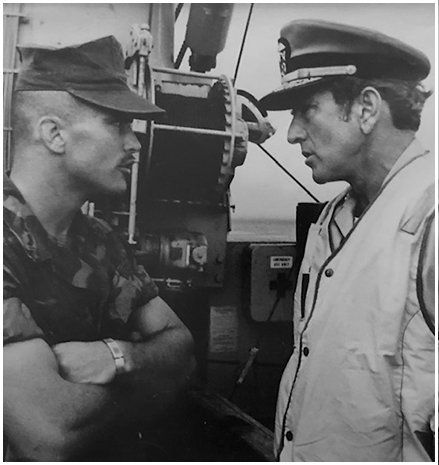

In 1968 he was promoted to vice admiral, ahead of 130 other officers, and was named the commander of naval forces in Vietnam.

Admiral Zumwalt, who had opposed American ground involvement in Vietnam since the early 1960's and would later write how ''I thought it was the wrong war, in the wrong place, at the wrong time,'' oversaw the ''brown water Navy.''

That was a flotilla of more than 1,000 patrol boats deployed in the Mekong Delta to deny Vietcong and North Vietnamese soldiers use of of the waterways.

Returning to Washington, Admiral Zumwalt took on another very formidable task, that of remaking the Navy.

''When I became chief of naval operations, racism and sexism were still an integral part of the Navy tradition,'' he recalled. There had never been a black admiral, black officers had few prospects for advancement, and women were not permitted to serve on ships.

In 1970, Admiral Zumwalt issued what he would call his most important directive, ''Equal Opportunity in the Navy.''

It required commanders of ships, bases and aircraft squadrons to appoint a minority member as a special assistant for minority affairs...

...demanded that the Navy fight housing discrimination against black sailors in cities where they were based...

...and required that books by and about black Americans must be made available in Navy libraries.

''There is no black Navy, no white Navy -- just one Navy -- the United States Navy,'' Admiral Zumwalt declared.

In another Z-Gram, women were permitted to serve on ships.

Because women were barred by law from ships that could be engaged in combat, a hospital ship, the Sanctuary, was designated in 1972 to break tradition, but not without protests from the wives of some enlisted men.

Admiral Zumwalt also wrote a Z-Gram he first called ''Mickey Mouse, Elimination of,'' but renamed ''Demeaning and Abrasive Regulations, Elimination of,'' an effort to remove some restrictions on sailors' personal freedom.

He gave a go-ahead for beards and mustaches, which were already permitted but generally frowned upon, and he allowed sailors to have sideburns, which he himself wore to the middle of the ear lobe, the longest length allowed.

He permitted sailors to wear civilian clothes on base when not on duty, authorized liquor in officers' quarters and beer in the barracks of senior enlisted personnel, liberalized overnight liberty policies and set 15 minutes as the maximum time a sailor should have to wait in line for anything.

While his changes gained wide attention, Admiral Zumwalt spent most of his time as chief of naval operations and a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff dealing with matters related to the cold war.

In an interview with Playboy magazine in June 1974, shortly before he retired, he remarked, ''There's a good deal of indecision as to whether I am a drooling-fang militarist or a bleeding-heart liberal.''

Speaking with reporters a month before the interview, Admiral Zumwalt said the Soviet Union had the capacity to control sea lanes in a crisis and foresaw a reversal of that situation only if Congress adequately financed a multibillion-dollar naval construction program he had instituted.

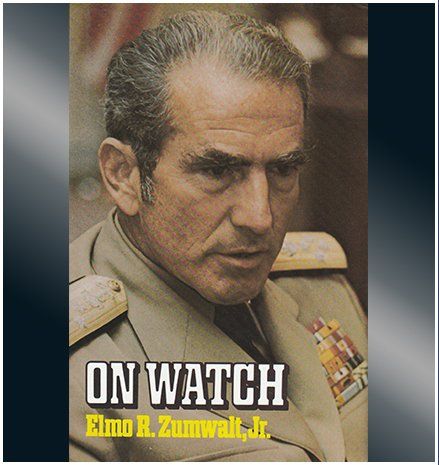

In his memoir ''On Watch'' (Quadrangle, 1976) he argued that the Russians had gained more from limitations on strategic weapons than the United States had.

Admiral Zumwalt ran as a Democrat for the Senate in Virginia in 1976 but was defeated by Senator Harry F. Byrd Jr., an independent. The admiral later served on many corporate boards.

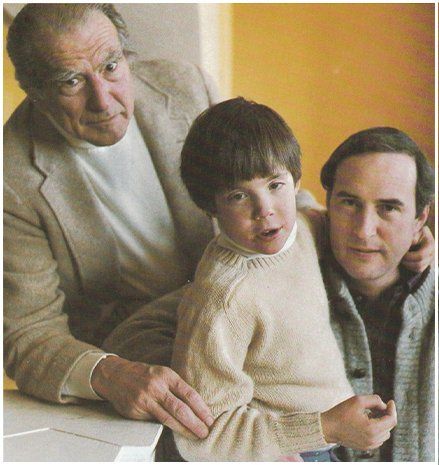

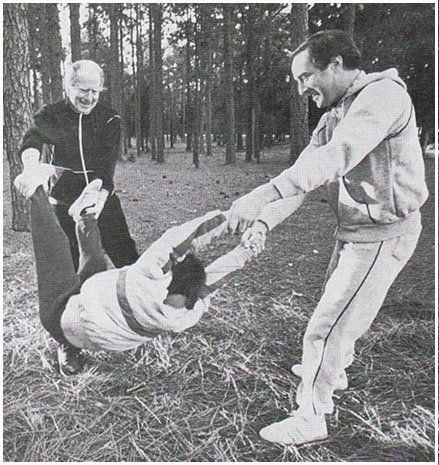

His son Elmo III left the Navy in 1970 and became a lawyer in North Carolina.

In 1983, he was stricken with lymphoma, a cancer of the lymphatic system. In 1985, doctors found that Elmo had Hodgkin's disease, an unrelated form of lymph-node cancer.

Elmo III's son, Elmo IV, known as Russell, was born in 1977, and suffered from a severe learning disability.

Admiral Zumwalt and his son attributed the cancers and the boy's learning disability to the Agent Orange defoliant.

Many Vietnam veterans had told of suffering from nervous disorders, cancers and skin problems and of having had children with serious birth defects, attributing these to the herbicide.

In My Father, My Son, Elmo Zumwalt III wrote: ''I do not second-guess the decisions Dad made in Vietnam, nor do I doubt for a minute that the saving of human life was always his first priority in his conduct of the war...

...I have the greatest love and admiration for him as a man, and the deepest respect for him as a military leader.''

Admiral Zumwalt wrote: ''Knowing what I know now, I still would have ordered the defoliation to achieve the objectives it did. But that does not ease the sorrow I feel for Elmo, or the anguish his illness, and Russell's disability, give me. It is the first thing I think of when I awake in the morning, and the last thing I remember when I go to sleep.''

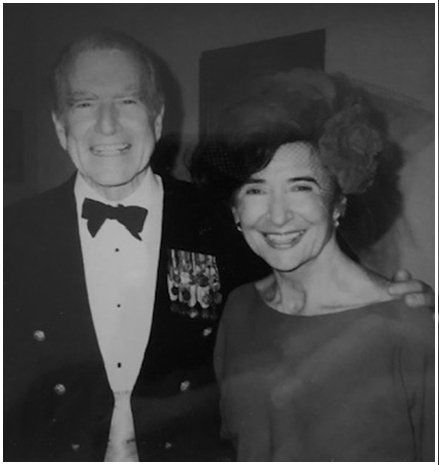

He is survived by his wife, Mouza Coutelais-du-Roche Zumwalt; a son, James, of Reston, Va.; two daughters, Anne Zumwalt of Longmeadow, Mass., and Mouzetta Zumwalt-Weathers of Cary, N.C.; a sister, Saralee Zumwalt Crow of Fresno, Calif.; a brother, James, of El Cajon, Calif., and six grandchildren,

In January 1998, President Clinton presented Admiral Zumwalt with the Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian award.

The Admiral was cited for fighting discrimination against minorities and women in the Navy and for his work on behalf of a foundation seeking bone-marrow donors for cancer patients.