OBITUARY

MOUZA COUTELAIS-DU-ROCHE ZUMWALT

22 January 1922 - 25 August 2005

Mouza Coutelais-du-Roche Zumwalt, 83, who partnered with her husband during his lengthy Navy career to make conditions better for military families and later joined him in building up a national bone-marrow registry, died Aug. 25 of congestive heart failure at her home in Arlington.

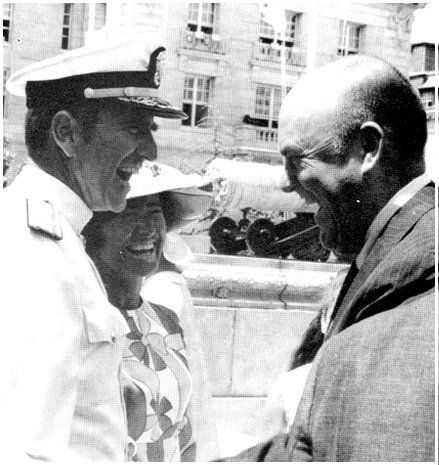

From the time she married naval officer Elmo R. Zumwalt Jr. in Shanghai in 1945 (after knowing him for three weeks) until the admiral's death in 2000, Mrs. Zumwalt engaged in the delicate role of supporting her husband's work from behind the scenes.

She was the consummate military spouse, dedicating her time to hosting military officials and counseling with other spouses, then lost a son to the consequences of her husband's wartime decision.

Elmo Russell Zumwalt Jr. and his wife-to-be, Mouza, had a whirlwind courtship, a story you see unfold in a movie but assume is just impossible in real life. They happened to meet at a party in Shanghai, China in 1945. She spoke Russian, Elmo didn't, and three weeks later they were married. Impossible? No.

She lived in 40 homes, raised four children, "kept the books and made life rich in tiny nooks," her husband wrote a few years ago in a poem titled "Tribute to A Golden Partner." You raised morale on many ships, Solved many family problems on ocean trips.

"She was an important member of the official party, meeting with Navy wives, American and allied, helping them with their problems, raising their spirits, and calling my attention to many things I had no other way of finding out about," Zumwalt said in his 1976 book "On Watch."

During her husband's tour of duty in Vietnam, Mrs. Zumwalt assisted the families of Navy prisoners of war and those missing in action.

She worked to raise money for the "Pigs and Chicken" program, which imported animals from the Philippines to provide protein to the Vietnamese people.

In the early 1970s, Mrs. Zumwalt sat in on focus groups dealing with race relations in the Navy. Her husband, as chief of naval operations, ordered the Navy to end racial discrimination and is credited with creating the modern Navy.

William S. Norman, a special assistant to Adm. Zumwalt in the 1970s, recalled that Mrs. Zumwalt never failed to ensure that Navy personnel participating in the focus groups, particularly minorities, brought their spouses.

"She became one of the foremost proponents of taking a whole approach" to the Navy experience and the family, Norman said. "She brought a very human touch."

Mouza Coutelais-du-Roche was born in Harbin, Manchuria, the daughter of a French businessman and a Russian mother.

Her parents had escaped from Siberia after the communist revolution and settled in a White Russian community in Harbin. She was 10 when the Japanese invaded Manchuria in 1932.

Just after high school in 1940, she accompanied her mother, who had cancer, to Beijing for an operation. They later went to Shanghai, where her mother could recuperate with relatives. After her mother died, the Japanese would not allow Mrs. Zumwalt to leave Shanghai.

She never saw her father, who had remained in Harbin, again.

In October 1945, when she was 22, she met a young U.S. Navy lieutenant at a dinner party at her aunt and uncle's home. When she entered the room, Zumwalt, who had been in Shanghai for just a week, was forever smitten.

"Tall and well-poised, she was smiling a smile of such radiance that the very room seemed suddenly transformed," he wrote in "On Watch."

She spoke no English, and Lt. Zumwalt spoke no Russian, although he had studied the language. He asked her if he could come back for Russian lessons. Within three weeks, Zumwalt asked her to marry him.

Three months later, the new Mrs. Zumwalt came to the United States on a Liberty ship, settling first in Seattle and then at her husband's family home in Tulare, Calif. She moved in and out of the Washington area frequently, making a home in Annandale in 1955.

During the Cold War, Mrs. Zumwalt endured prejudice because of her Russian background. People mocked her accent, and some steered clear of her during the McCarthy era, her children said.

Such experiences informed her own quiet and unrelenting advocacy to eliminate racial discrimination in the Navy.

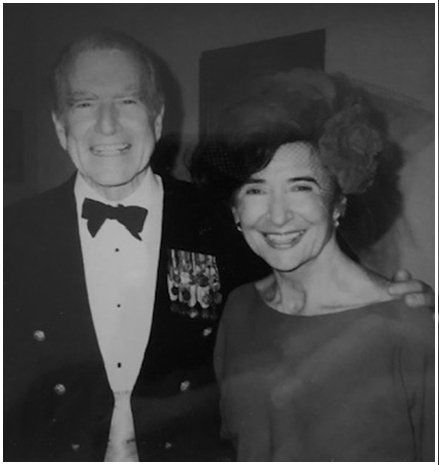

Over the years, she was honored for her timely and effective support of her husband's career, including by the Navy's "ombudsman program" and Operation Helping Hand, a military service group.

In 1971, she christened the USS Brewton.

When President Bill Clinton presented Adm. Zumwalt with the Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian award, in 1998, the admiral said that half of it should go to his wife.

In 1983, her first child, Elmo R. Zumwalt III, was found to have lymphoma. When he died in 1988, his death was attributed to the effects of Agent Orange. He had been a lieutenant in the Navy commanding a Swift boat in Vietnam when his father ordered the spraying of the potent chemical agent.

"She understood a nation's need for a military to answer the call," said her other son, retired Marine Corps Lt. Col. James G. Zumwalt II of Herndon. "She understood the risks."

Later, she joined her husband in starting the Marrow Foundation to raise funds for the National Marrow Donor Program. The Mouza Zumwalt Good Deed Fund was established in November to support self-employed people going through the transplant process.

She enjoyed classical music and her skills on the piano were close to the level of a concert pianist, said her daughter, Mouzetta Zumwalt-Weathers of Cary, N.C. She also loved old movies.

In addition to her son and her daughter, survivors include another daughter, Ann Zumwalt Coppola of Longmeadow, Mass.; and six grandchildren.